Photo of Serena Hotel (Courtesy of Time Magazine: Losing Kabul: A Bomber's Legacy)

The Arrival

We first landed in a C-17 in Kabul at the International Airport. There were no limos waiting; no meet and greet holding signs -- just a thick haze of dust and humidity so thick you could slice it with a saif (curved, 19th century Arabian sword) and spread it on a chapati.

Kabul International -- from 1979 to 1989, the airport was run by the Soviet Union Red Army. After the invasion, the airport was used exclusively by the US Armed Forces and ISAF. After removal of the UN sanctions in 2002, the airport was opened up to civilian airlines. |

We were methodically whisked away in a convoy of Humvees sandwiched between two armored personnel carriers. NATO Soldiers with machine guns kept a vigilant watch for insurgents or anything suspicious.

Who We Were

We were part of an advisory group for the NATO Supreme Allied Commander. Our boss, General Craddock, as NATO's top military commander oversaw the progress in Afghanistan. We would be receiving many briefs and updates during our short visit.

SHAPE Headquarters in Mons, Belgium |

Who Met Us

Comprised of forces from over 25 nations, they were part of the International Security Assistance Force . Responsible at first for the security around Kabul, their mission had now expanded to the whole of Afghanistan, a conflict that we had come to observe.

A War we Had Previously Won

In December 2001, the world looked extremely different. The US had essentially shocked, awed and terminated the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, and there was talk about how the country would evolve into a pro-American nation providing access easy access for new oil pipelines.

Focus on Iraq

Meanwhile, the Bush Administration focused on Iraq and the demolition of the Saddam Hussein regime. The US wanted to put Afghanistan behind us, so they redeployed many of their forces to Iraq. Unfortunately, the real enemy and the perpetrators of 9/11 was the Taliban.

The Sad Truth

Sadly, Afghanistan had become America's forgotten war. Currently, America was tied down and absorbed in the intricacies of Iraq. Meanwhile, in this forgotten country of the Taliban and Heroin, NATO forces had confronted a resurgent Taliban especially in the southern Helmand province where the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) were deeply embedded.

Sadly, Afghanistan had become America's forgotten war. Currently, America was tied down and absorbed in the intricacies of Iraq. Meanwhile, in this forgotten country of the Taliban and Heroin, NATO forces had confronted a resurgent Taliban especially in the southern Helmand province where the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) were deeply embedded.

The Desert Limo

Since it's implementation, the Humvee has served as the backbone for U.S. forces worldwide.

Over the years, the Humvee has evolved from a venerable troop carrier in the Persian Gulf War, Kosovo and Bosnia to a more heavily armored vehicle battling bomb-wielding insurgents in the shifting global war on terror urban combat.

The Humvee is heavily armored, but it has a flat, vulnerable bottom and its low to the ground making it vulnerable to IED attacks.

Roadside bombs are among the leading killers of troops in Iraq -- a grim statistic that could be drastically improved once the deployment of the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles is fully implemented.

Sadly, a total MRAP replacement cannot come soon enough -- may never come before our troops go home.

Already, casualties in Iraq this summer had significantly improved due to the improved armor and design of the MRAP.

This is encouraging, but we should have been ready before we headed out in harm's way.

We kept our helmets strapped firmly, our body armor tight, like it was going to run away if we didn't keep it buttoned down.

And as I looked out the blast-resistant windows, I could see concrete security barriers, blast walls, deep trenches, barbed wire -- all the vestiges of war that provided some protection against the surging insurgency.

It was true that these walls added to the congestion and traffic jams. But in this high-terror environment of random and almost weekly suicide attacks, these barriers of limited but viable protection seemed called for.

They kept the coalition forces safer, they allowed aid workers to carry out their duties, but also served as a physical and psychological distance from the local population they we were deployed to work with.

I felt relatively secure, safe in a foreign land marked by discord and lurking danger.

We drove towards the city center. Normally the majority of the vehicles would comprise of NATO convoys tearing through the city at breakneck speed like it was the Santa Monica Freeway.

With all the busses, vehicles, sedans, bicycles, carts, with dozens of round abouts and absolutely no traffic lights, congestion was a grueling finger cramping nightmare.

Today, we were given top priority for safety, and ISAF would allocate all resources possible to ensure we were kept safe as we rolled down the streets of Kabul.

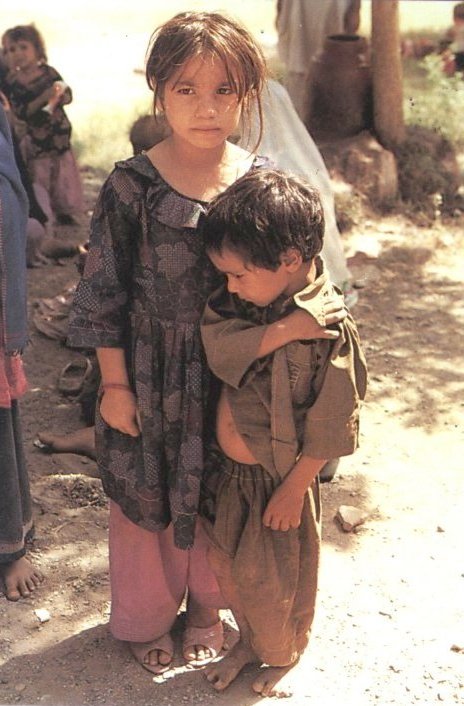

The Children

However, at this moment, the roads were secure and the only people we saw were busy shopkeepers and the empty look of children waving, begging and staring hopelessly into our humvees. Seeing kids was definitely a welcome sight. They were indigent, many without families or homes, some living in shelters, some not getting a proper education.

But deep down inside, I sensed that they were amazing human souls, displaced, downtrodden but full of spirit and energy.

But inside the heavily-armored Humvee, I also felt displaced, almost a world and distant land away

For a striking moment, I wished we could stop in our tracks, get out in the fresh air and give these children a warm, soft hug. Why not, without candy or change, that was the only thing I could offer or perhaps just a chuckle, a banter for hope for a brighter future one day.

I remembered poignant images of The Kite Runner and the unconditional love and commitment Hassan had for Amir, and how Amir eventually made up for his past failures and returned home to help his old friend Hassan, whose son is in trouble.

Video shot by Monk Films in 2006 showing the "dirt paths and wild streets" of Kabul.

The Entrance

In Kabul, speed is survival. If we are moving fast, the enemy will have less time to target us. I sat erect, scanning our surroundings intently. If we were to get attacked, I at least wanted to get a chance to see the eyeballs of the enemy.

What a sigh of relief. No where on this land was fully safe, but for now we could unshed our body armor and loosen up our chin straps.

The Troops

We stayed there through dinner, and while we waited, we spoke to some young Brits about duty in Afghanistan. They shared their stories: their gripes, their victories. They missed their families, their wives and girlfriends, their country, but most ardently their alcohol. Meanwhile German troops could drink beer and wine. British and US forces had to settle for coke or red bull.

At the Headquarters, there are more than 2200 service members from 42 NATO nations. Everyone seemed to work well and even socialize well together. It appeared that they were willing to set aside any cultural differences and even make a strong attempt to learn each other's norms and nuances.

The Drug Problem

We also talked informally about the drug problem -- no, not within NATO. The Heroin trade was serious in this impoverished nation. Afghanistan is the world's largest exporter of heroin. It is the country's main cash crop. There is more heroin that is exported in Afghanistan than cocaine is produced in Colombia. There were even reports that children were becoming addicted to cocaine.

Although some of the three billion dollars annual revenues goes back to the the local economy such as jobs for farmers and reconstruction, the vast majority of the revenue is funneled to the Taliban.

Though Opium poppies grow in almost every province of Afghanistan, the problem area is the south. In the Helmand province, where the Taliban maintains a stronghold, they are said to levy a 40% tax (1) on opium cultivation and trafficking.

In addition, many of the security forces have turned into heavy opium users

After the meal and the chat, it was now time to check into the safe confines of the Serena Hotel.

Safe and Serena

Situated amidst bombed-out buildings, the Serena is the modern symbol of capitalism and safety making a bold attempt to flee from and flaunt the suppression of the insurgency.

The Serena's design is stylish and the service is first-rate superb. When walking in, I felt like I was in the magnanimous confines of the Marriott or a Hilton in Bahrain, Istanbul or any world-class city. The hotel is as safe as you can get. You go through a full security screening each time you enter and no one is allowed to drive straight in from the street.

Inside the magnificent confines of this 5-star hotel, hosts a beautiful courtyard and a luxurious swimming pool -- the only feasible place to take a dip in the whole city of Kabul.

The price for a room averages $250 per night, which is very steep considering that Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the world. But it was worth every single Afghani.

The Serena Hotel is a an oasis of safety for the many UN workers, contractors, journalists and aid workers. But even this sanctuary can be infiltrated. For meals, the buffets are delicious and the fruit juices are divine. There is no alcohol, and some of the guests I talked to took an issue to that.

Earlier in the year, seven people were killed as Taliban stormed into the Serena Hotel. The attackers struck with grenades, guns and at least one suicide bomb and were targeting the Norwegian foreign minister who escaped unharmed.

An Afghan policeman stand guard after the attack. (AFP: Hossaini Massoud)

Tonight we will spend a comfortable, restful evening in the safe confines of the most luxurious hotel this city will ever

Kabul. Tomorrow we are off to the mountain pass that links Afghanistan with Pakistan, the ancient and strategic Khyber Pass.

More raw and vivid scenes of Kabul -- its streets, its people, its culture shot by Ottawa Citizen reporter Andrew Mayeda in 2007.

(1) Global Terrorism Analysis, The Jamestown Foundation, May 10 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment